The Ontario Traffic Council has produced a new Bicycle Facilities guide. It was produced with help from Vélo Québec, which has the experience of Québec's extensive cycling facilities, and Alta Planning and Design which has been at the forefront of a new generation of protected bicycle facilities in North America. It is a promising document, but it still falls short of high water mark that is Dutch bicycle facilities standards. This much we learn from David Hembrow of A view from the cycle path, who explained how even this updated Ontario standard falls short of Dutch expectations for their own facilities. It reveals that even though the concept of providing protected facilities that appeal to all ages and abilities is now here, it has yet to fully permeate planning.

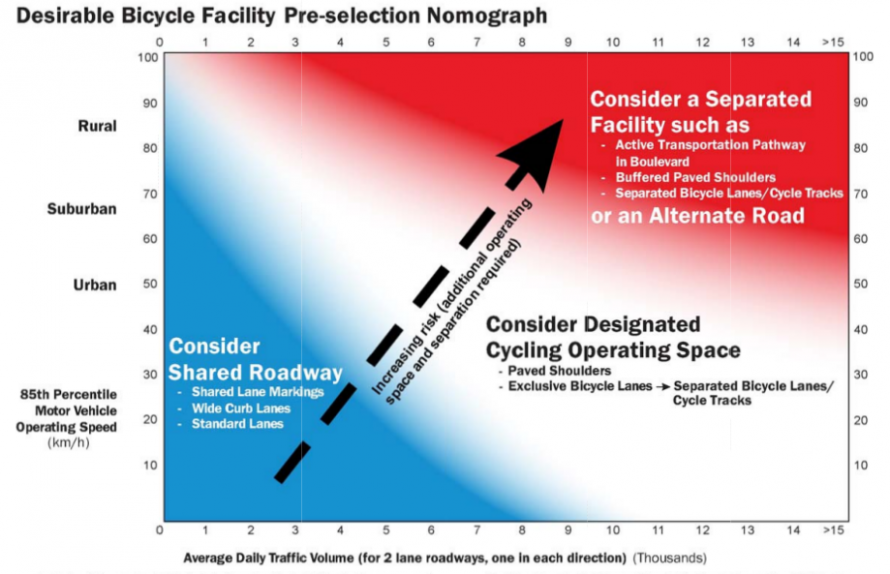

The language of the document is slippery. Some of it sounds quite reasonable on an initial reading, but when you look closely it becomes obvious that the authors have rather low aspirations for cycling. There is an expectation that cyclists can share the roadway when both speeds and traffic volumes are at higher levels than we would experience. The authors think that it is only necessary to "consider" building an on-road cycle lane even speeds of up to 100 km/h. The language of the document betrays the lack of ambition for cycling.

From the graph streets like Richmond and Adelaide would "qualify" for protected bicycle facilities, but just barely because the traffic is quite high. This graph might exclude a lot of streets that in Europe they would consider excellent candidates for separated facilities. These decisions are mostly arbitrary so perhaps the traffic planners could err on the side of making streets more comfortable.

The manual is not particularly innovative but reflects the state of the art in North America, not surprising given the consultants come from across the continent. For those of us doing cycling advocacy in North America it's good to have an outside critique to help us keep an eye on a distant goal. We are mindful that we want to celebrate our wins, big and small, lest we come off as ungrateful, something with which Hembrow doesn't have to concern himself. By being the first Ontario document to explicitly allow for protected bicycle lanes this is a real step forward. But Hembrow's excellently placed skewer of North American traffic planners blind spots shows just how far we still have to go.