The Harbord and Hoskin bike route as it currently exists is not good enough to convince a large percentage of people to bike. For that to happen, as many other cities have found out, physically separated bike facilities make cycling much more popular as well as safer.

Even though Harbord and Hoskin is a popular bike route (partly by funneling people from other streets), its painted bike lanes and sharrows only attract a small portion of Torontonians. Being just paint makes it easy for motorists to park in, and sharrows do nothing to prevent cyclists from having to struggle and squeeze between car doors and fast moving traffic.

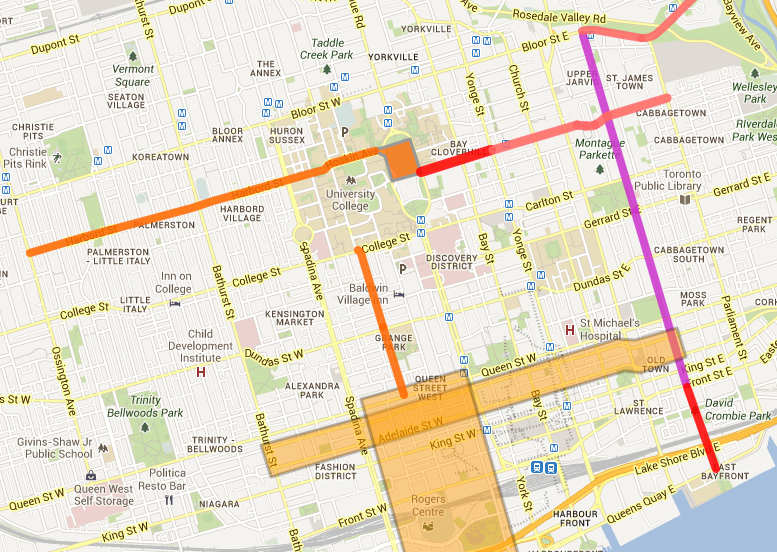

We've now got an opportunity to showcase a new, better way of building bike infrastructure. Harbord to Wellesley, if all goes well, from Ossington to Parliament will have protected bike lanes along its entire length by the end of 2014.

Toronto is hardly being radical by building protected bike lanes. Heck, even Lincoln Nebraska is building a bidirectional cycle track!

Lincoln, Nebraska gets its own cycle tracks

Attracting the "interested but concerned"

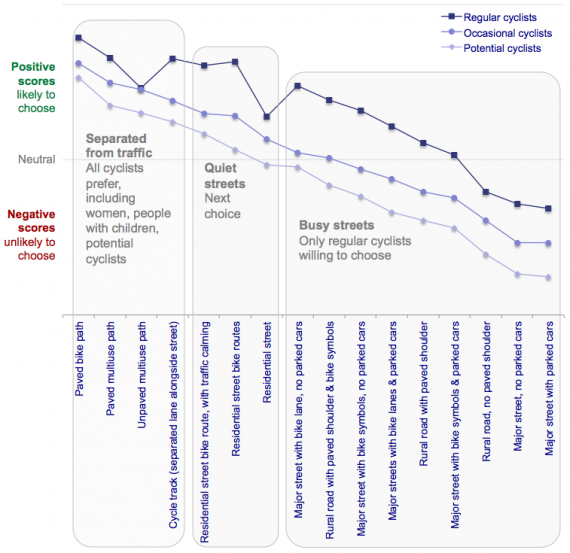

The Portland Bureau of Transportation in a survey found a "interested but concerned" group of potential cyclists that made up 60% of the population. This is a group that is willing to bike (unlike the 30% who would never consider cycling) but have been turned down by the poor state of infrastructure. Compare that 60% to the 1% of the strong and fearless and the 7% of the enthused and confident and it makes me think how vocal cyclists now often fail to think of how different things would be if even half the potential cyclists could be converted.

For the interested but concerned person, this is what is needed to convince them to hop on a bike on busy urban roads - separation from motor vehicles. These are people - young, old and unsure - who are uncomfortable riding in busy traffic and will only consider cycling as a regular activity if they get more infrastructure.

This group of potential cyclists rank separation from traffic higher than existing cyclists. The preference study at UBC's Cycling in Cities showed that for potential cyclists, having separated bike lanes or quiet bike boulevards was important and were unwilling to ride on major streets with parked cars and just painted bike lanes. It's interesting to note that even regular cyclists ranked cycle tracks highly but were much more comfortable riding on major streets with painted bike lanes.

Where hardcore cyclists are comfortable riding in mixed traffic next to large trucks and car doors (though even this changes as we get older), the potential cyclists are most comfortable on recreational bike paths and with clear separation from motorized traffic. While hardcore cyclists tend to be dominated by men, potential cyclists represent the larger population in gender, age and ability.

The City still tends to listen primarily to the 2% hardcore cyclists when building new bike facilities. The idea for protected bike lanes on Harbord (and Sherbourne and Richmond/Adelaide), however, came from outside the hardcore group. It was borne of people who had seen cities like Amsterdam or New York and saw the potential in Toronto. It was a major push to get City cycling staff and cycling advocates to think beyond painted bike lanes that provide next to no comfort or protection and focus more on the concerns the 60% and come up with strategies for building what is needed.

Protected bike lanes on Harbord and Hoskin will help provide a mind-shift among Torontonians, improving infrastructure for the majority.

Harbord/Hoskins needs more than just paint

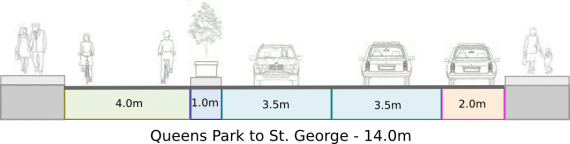

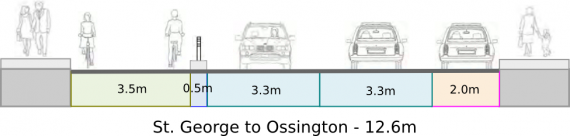

Some preliminary drawing and figures were presented at the recent open house.

From Queens Park to St. George

From St. George to Ossington

Harbord and Hoskins cycle tracks will be a great improvement for those streets where speeding along stretches is still common, drivers routinely park in the bike lanes, and where a large stretch doesn't even have bike lanes.

Protected bike lanes are safer

But it's not just that people prefer more separation on streets like Harbord, it has also been shown to be safer than just painted bike lanes. After NYCDOT build cycle tracks on Prospect Park in Brooklyn they found a number of benefits, more so than what a painted bike lane would provide:

- Speeding is down

- Sidewalk cycling is down

- Crashes are down

- More cyclists of all ages are using it

The protected bike lanes will also provide specific benefits of vastly improving the intersection at Queens Park and Hoskin. What is currently an uncomfortable and unsafe intersection where cyclists and pedestrians have to deal with high speed traffic will be redesigned so cyclists can avoid having to try to cross multiple lanes of fast traffic.

And let's not forget that we finally have the political will to fill in the missing bike lane along Harbord, where cyclists have nothing but a narrow space between the doors and moving traffic. This requires politicians willing to risk the wrath of merchants.

Both Councillors Layton and Vaughan have come out supporting the Harbord separated bike lanes. Along with public works Chair Minnan-Wong, the support for Harbord is across the political spectrum. This is pretty rare in cycling advocacy. Even Mayor Miller missed his chance to build major bike lanes. Politics is the art of the possible and if this opportunity is not taken, it will be much harder to build another chance.

With such broad support the chance of getting protected bike lanes along the longest bike route through central Toronto just might be possible.