Take the Lane!

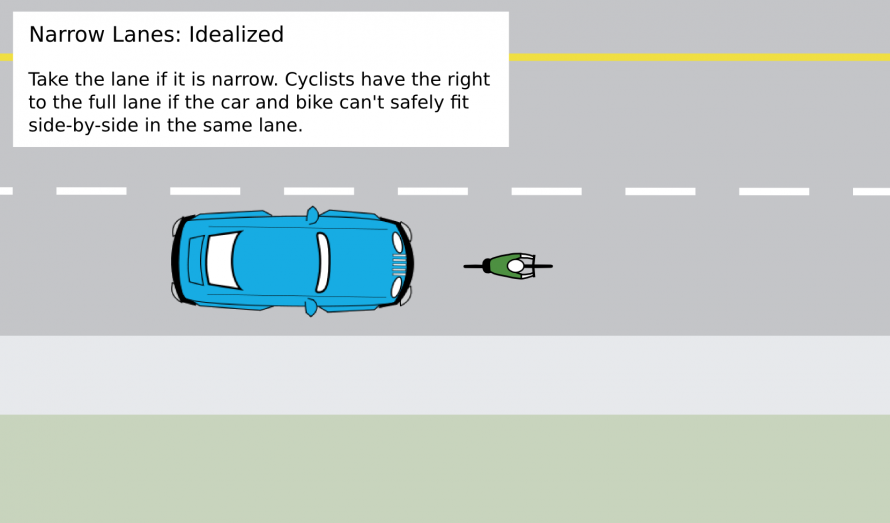

You may have been advised that the best way to be safe is to take the lane. Everyone from public space advocates to CAN-BIKE instructors to the League of American Bicyclists and CyclingSavvy promote taking the lane when a cyclist can't safely share the lane with a car. While taking the lane can be an effective strategy as a cyclist, it should not be taken as helpful in all situations. In fact, in many cases it may cause more problems than it supposedly solves.

Lane Position on a Wide Road

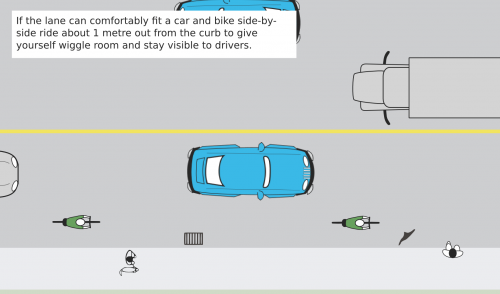

All the main North American cycling courses discuss lane position and largely agree that when lanes are wide enough the cyclist can easily share the lane with a motorist, so long as the cyclist rides far enough from the curb (about 1 metre out). The League of American Bicyclists states that a cyclist should:

- Ride in the right third of the right-most lane that goes in the direction you are going

- Take the entire lane if traveling the same speed as traffic or in a narrow lane

According to my CAN-BIKE handbook, the general rule is to "maintain one metre from the curb or from parked cars". But that rule only applies when there is enough room for the car and bike side by side. "If the lane is too narrow or there is an obstruction that narrows the lane then take the whole lane."

CyclingSavvy is more dogmatic in insisting that the lane be at least 14 feet wide in order to safely share. Very few lanes in Toronto meet this criteria. By any of the courses criteria, a cyclist would find themselves on a road that the courses would advise them to take the lane. But there's a problem with that simplistic prescription.

When taking the lane won't work

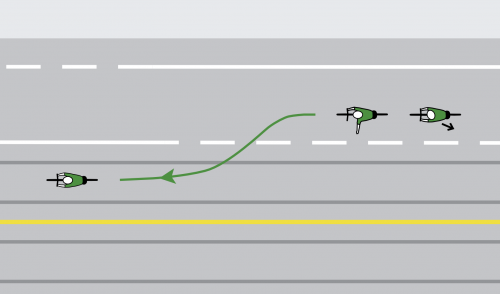

[img_assist|nid=4571|title=|desc=|link=node|align=center|width=500|height=294]

In the top diagram (I used the icons from the Toronto Cycling Map) we see how taking the lane is supposed to work. The lane is too narrow to share so the cyclist takes the lane. This, according to the courses, sends a message to the traffic behind that they should safely pass in the next lane instead of squeezing the cyclist into the curb. When practised in a large city like Toronto, results will be mixed. There will be drivers who willingly wait behind until it is safe to pass. In my experience, however, it is just as likely that the driver is impatient or annoyed. And, once in a while, we will even encounter an enraged driver.

The cyclist, particularly if they are young or elderly, will feel intimidated or be threatened by drivers behind them. Most of the drivers will keep calm and even if they are annoyed are willing to wait. But it's a crap shoot if we'll meet a driver who openly threatens by driving closely, swearing at the cyclist, revving their engine or honking, or even passing as closely as possible to "teach the cyclist a lesson". It's those situations that can leave even seasoned cyclists shaking, stressed or even injured if the driver manages to sideswipe. In those cases, any safety benefit of taking the lane is lost.

These drivers are not evil people out to get cyclists. Rather, annoyance builds up to such an extent from frustrating downtown traffic that they are more likely to get road rage and take it out on someone on a bike. Particularly if they've been conditioned to see cyclists as not having a "right" to the road and see them as blocking their path. Road rage can cause people to take risks that they wouldn't normally take when they are calm. It's not a medical condition per se, but Wikipedia mentions there is a link to "Intermittent explosive disorder", which is listed as a medical condition under impulse control disorder.

You can create your own experiment on the stretch of Shaw Street from Dundas to Queen. The lane is too narrow between the parked cars and the central meridian to share. According to the theory the best thing the cyclist can do is take the lane. Having ridden this stretch many times I have come to dread the sound of an approaching car behind me. Mostly the driver will wait, but a high number of them will start honking or even find any gap in the parking to try to make a quick pass.

Very few people would never get stressed or have some fear building up. Can we read the mind of the motorist? The only evidence of their intentions is by their actions. If they start honking or revving their engines they might be trying to just intimidate but who knows. It's a crap shoot.

In this situation we would best deal with it by pulling over and quickly getting out of the way of the driver, hoping that they'll just move on instead of also stopping to harass us.

Toronto's not exceptional in having frustrated drivers. As Easy as Riding a Bike notes that "[n]o-one seems to have told U.K. drivers about it. Putting yourself out in the middle [of the] road can, in my experience, appear to some drivers as an act of deliberate provocation. They don’t have a clue what you are doing." And Volespeed goes even further, stating that Taking the Lane, or "primary position", embodies a dishonesty.

The phrase, I believe, originally came from motorcycle training. But as applied to cycling, it doesn't make the same sense as it does in motorcycling. The "primary position" cannot be the primary position for cyclists on roads where the speeds are almost always far in excess of most people's top cycling speed. Some fit, young cyclists can cycle at 20 mph on the flat, but few of our roads have a 20mph limit, and in the more normal 30-limit urban areas, typical speeds are up to 45, in reality, where the roads can take it. So even fast cyclists stand little chance of maintaining the primary position most of the time. A more normal cycling speed, even with the current cadre of cyclists, would be 10–15mph. For them, in being sold this "primary position" theory, they are clearly being sold a lie. And this is to say nothing of the currently largely-excluded groups that we want to get on bikes: children, the unfit and the elderly, who are not going to do more than about 8 mph.

Fast suburban but narrow lanes

In Toronto's suburbs most arterial streets have high average speeds of greater than 60 km/h. Many of these suburban arterial lanes are narrow. It rarely make sense to take the lane on these streets. The high speeds and the fact that no driver is expecting to see a slow cyclist means that taking the lane can be inviting danger. In fact, CAN-BIKE teaches that on fast arterial streets that cyclists should actually ride close to the curb - 1/3 metre instead of the typical 1 metre.

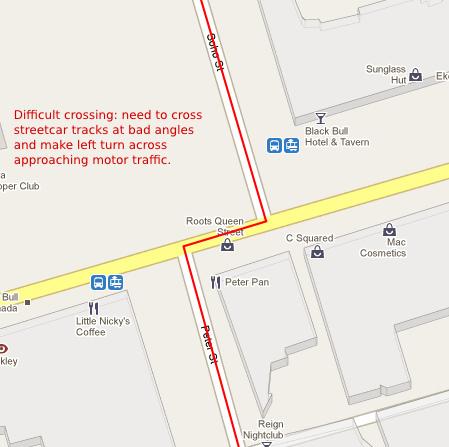

Crowded downtown streets

In downtown Toronto the situation is different. We have arterial roads with on-street parking, narrow lanes, lots of traffic and often streetcar tracks. Streets like King, Queen, Dundas, Ossington, Dovercourt, College and Bloor. It would be quite hard for the typical Toronto cyclist to avoid these streets completely. What cycling courses don't teach is how the average cyclist can best deal with these streets. In theory, it would seem that taking the lane is the best and only option. The sanest approach to riding such streets is often to ride somewhere between the parked cars and the middle travel lane.

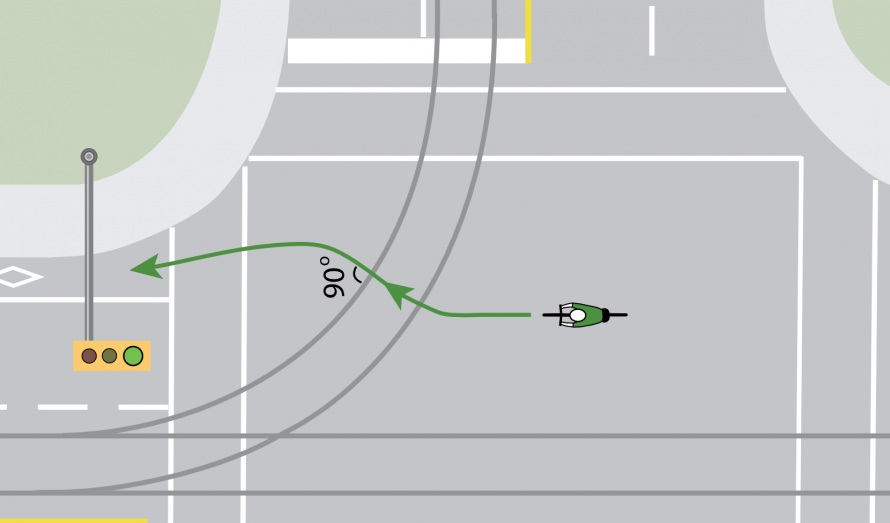

[img_assist|nid=4529|title=|desc=|link=node|align=center|width=500|height=294]

The above diagram is a typical streetcar street outside of rush hour: parking on both sides of the street and the middle travel lane is busy. Using the Take the Lane principle the best and only correct position would be A. This would be the best way to both avoid opening car doors and overtaking cars. In theory. In reality very few cyclists can ride fast enough to keep up with the peak speeds of cars. Cyclists may be able to easily keep up with motorists because cars often get stuck behind other cars, but when there is open road in front, all too often a cyclist who is taking the lane is seen by motorists as trying to deliberately anger them by blocking their path. These drivers will soon be itching to pass and will often pass quickly and unsafely. Riding out in the middle in front of a line of frustrated drivers is emotionally stressful. The average person can only handle so much intimidation from drivers.

Even if you're one of the very rare persons with an exceptionally thick skin that can take all matter of verbal abuse and threatening behaviour, you'll soon feel like a schmuck as you get stuck behind backed up car traffic while the rest of the cyclists filter up in the right lane.

99% (give or take) of all downtown cyclists ride in position B most of the time. It is a position that makes the best of a bad situation. I find that the best position is on the left edge of the right lane, as far as possible from opening car doors with enough room on the left for cars to pass in the left lane. It's not ideal but such is life living in a car-centric town.

Which position is safer?

Some educators claim that taking the lane is safer than staying to the side. The claim is that a cyclist is more likely to be side swiped than struck from behind. There are two issues with this conclusion: one, the statistics don't back this up, and two, even if there was evidence of this, the studies don't report what position the cyclist had taken on the roadway prior to their crash. From the available evidence we can't conclude that cyclists out in the middle of the lane are less likely to be struck than those on the side.

One of the best-known and comprehensive cycling safety studies was done in 1994 by Alan Wachtel and Diana Lewiston. They noted that being struck from behind accounted for only 5 of the 314 (1.6%) bicycle-motor vehicle collisions they studied. But side swipes were also only at 8 out of 314 (2.5%). It's not clear if either number is statistically significant., though given that most cyclists I've observed tend to stick to the curb, it doesn't seem to be a high number at all.

There is a further problem with trying to using Wachtel-Lewiston study to support taking the lane. The study doesn't report the position in the lane of the cyclist before they struck, only if they were on the roadway or sidewalk. Thus it's unclear if taking the lane will make any difference in either being struck from behind or in being side swiped.

I have had close calls being close to the curb as well as while trying to take the lane, for different reasons. The cyclist does not have complete control over the reaction of the driver. By being close to the curb a driver may see it as an opening and squeeze the cyclist to the edge. But by taking the lane a frustrated/enraged driver may find the first opportunity to pass and then pass as closely as possible so as to teach the cyclist a lesson. I've experienced both.

Two other studies are not much help either. The Toronto car-bike collision study 2003 and the major 1977 Kenneth Cross study (clearly getting a bit dated) only reported on collisions where the motorists were overtaking, and did not differentiating between "side swipes" and struck from behind. We can't draw a conclusion from either study that we're better off taking the lane. In the Toronto study the top three collisions downtown in terms of severity of injury were 'Motorists Overtaking', ‘Dooring,’ and 'Motorist Left-Turn Facing Cyclist'. Being more visible can likely decrease the risk of any of these, though it's unclear how far out a cyclist should ride. In the case of dooring, riding far enough out to be able to quickly avoid opening car doors is a good idea.

Holding to the dogma

Cycling education in North America still doggedly sticks to the take the lane philosophy with varying degrees of exceptions. These courses are mostly based on a cookie-cutter "vehicular cycling" philosophy that was developed in the 1970s by mostly fit, young people (the "father" of this movement was John Forester). Courses like CAN-BIKE or Cycling Savvy owe their roots to this movement, and continue to mostly stick to a worldview that is not always based on the best evidence. Instead there is a lot of the anecdotal evidence of a sub-group of people who were at the top of their faculties and fitness (obviously they're all elderly now). That these courses continue to hold whole-heartedly to this worldview does a large disservice to all the people who don't fit into that sub-group, particularly to those who are not in the prime of their life or fitness, or are too young.

There aren't hard and fast rules to cycling safely; there are many Toronto streets downtown and in the suburbs that defy the simple lessons taught in the cycling courses. Cycling educators have also tended to ignore or dismiss cycling infrastructure that makes it easier for different traffic modes to coexist. I have found a course like CAN-BIKE useful, and in fact, I had taught CAN-BIKE for a number of years. But I think it's time for CAN-BIKE to be rebuilt taking into account the wealth of knowledge coming out of Europe and increasingly in North America as young and old, able and disabled start cycling in our cities.

Cycling education shouldn't be about going fast, and safety should be available to the slow and fast, young and old. Education is also an alternative to improved cycling infrastructure. Really, we want both.

I hope to be looking at other cycling education themes in future posts and look at how we can think beyond a pure "vehicular cycling", one that acknowledges the inadequate infrastructure and that cyclists need to find a way to make good of a bad situation until things improve in our cities.