In a funny twist, a handful of Harbord businesses have become bedfellows with a couple of activists, including one who previously fought for Harbord bike lanes, and are now trying to stop separated bidirectional bike lanes on Harbord. Meanwhile activist group Cycle Toronto has launched their own petition buttressing support for the lanes.

We the undersigned

On the anti petition side we've got a guy named Marko and a self-described "carmudgenly" cycling activist, Hamish Wilson. Their petition asks Councillors Layton and Vaughan to halt the plan for bidirectional separated bike lanes on Harbord, calling them "dangerous", citing Transport Canada (1). A reader sent me the photo above of the petition displayed prominently at Harbord Bakery and said they saw about 100 signatures (and there might be another hundred or so signatures captured elsewhere).

Meanwhile Cycle Toronto's petition in support of the separated bike lanes has over 220 signatures (here and in paper versions going around).

But even this isn't the only petition. In 2010, a petition for the separated bike lane network was sent to the public works committee and included the call to "complete and separate the Wellesley/Harbord bicycle lanes system and end the gaps in the system at Queens Park and on Harbord." It has about 150 signatures on it. A number of organizations and groups also sent letters of support at that time which if we counted all the people involved in those groups would add up to thousands of people (2).

Both councillors for Ward 19 and 20, Councillor Mike Layton and Councillor Adam Vaughan, have stated publicly that they support the separated bike lanes on Harbord. We'll see what these petitions mean for their continued support.

The centre of the battle

This is what it looks like near the Harbord Bakery currently: squeezing between moving and parked cars, and token sharrows. And where there are bike lanes they are typically treated by motorists as free parking.

I'm not alone in that estimation. People who signed the Cycle Toronto petition had similar comments. From Bradley:

I frequently bike on Harbord, and although it is a very good street for cycling, I don't believe Sharrows do anything to help cyclists, and separated lanes are the way to go to improve cycling in Toronto today and in the future. Bidirectional lanes are my preferred option for both safety and ease of movement, allowing easier passing and a mix of cyclists of different skill and comfort levels.

And from Jennifer:

I live in the West end and commute by bicycle daily along Harbord to the downtown core. Harbord/Hoskins is a well used biking route. While the current painted lines offer cyclists some amount of protection, the fact that cyclists must ride in between parked cars (which are often pulling out into traffic) and the busy roadway, and the busyness of the bike lanes, makes this route a perfect option for separated bidirectional lanes. I also use the Sherbourne Street bike route on occasion and the painted separated route makes cycling much more visible and predictable for cyclists, motorists and pedestrians.

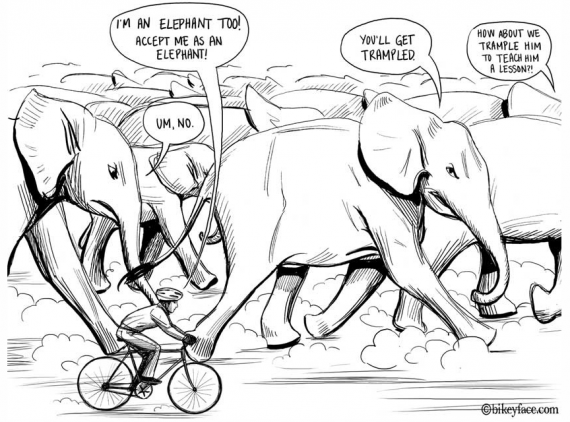

These responses are typical of people who are not "hardcore" cyclists used to mixing it up with the elephant herd. Most people, studies have shown, prefer separation.

Running with the elephants by bikeyface.com

I don't think the anti group has clarified that they are fighting for a street that is already frustrating, unsafe and not even connected. Is that the kind of street they think most cyclists prefer? If so they're deluded.

Strange bedfellows

The businesses opposed to this plan seem to be led by the owners of the Harbord Bakery and Neil Wright, Chair of the Harbord BIA. They've been vocally opposed to bike lanes for decades. In the 1990s they fought off bike lanes in their domain and managed to do it again a few years ago.

I had thought that this opposition had softened when I attended a public meeting last fall organized by Councillor Vaughan, writing in my blog post that it was a mostly positive, albeit lukewarm, response from business. In fact, the owner of the Harbord Bakery even stood up to announce they have always been pro-bike, they had been one of first to install a bike rack! Alas, it was not to be. Instead a strange alliance formed to oppose the proposal.

Hamish Wilson was a key person in fighting for a complete Harbord bike lane in the 1990s. Wilson and a number of other activists worked doggedly for the bike lane. They measured out the street width to ensure that bike lanes could fit, talked to merchants, worked with City staff. But in the end City staff caved in to business concerns about losing some curbside parking and left two disjointed bike lanes to the east and west. And now the activist is fighting against bike lanes.

Why the opposition?

The BIA Chair and the Harbord Bakery seem to be dead set against bike lanes in any form, perhaps thinking that the bike lanes will hurt their businesses. But with New York City and elsewhere experiencing booming business revenues where bike lanes were built (revenues up 49% compared to 3% elsewhere), this has become more of an outdated notion. We now know that cyclists have more disposable income and shop more often).

It's easy to imagine why the Harbord businesses are opposed even though misguided, but I can't really understand the passion with which Marko and Hamish are fighting against this proposal. Perhaps it's fear of the unknown. In cities where bidirectional has been built I have found no such outcry.

Risky game

What the petition writers gloss over is that risk is always relative risk. We can't just label something "dangerous" and something else "safe". Is climbing a ladder "dangerous" or "safe"? It doesn't make sense to ask it that way. Instead we should be comparing the risk to something else. For instance, is climbing a ladder more or less risky than taking a shower? Likewise is a bidirectional separated bike lane riskier than riding next to the threat of car doors opening? To answer that question we need real data, not just opinion.

The UBC Cycling in Cities studies, for instance, are helpful in that they have shown that separated bike lanes are significantly safer than bike lanes next to parked cars. And Dr. Lusk's studies of separated bike lanes in Montreal showed that not only is cycling on bidirectional separated bike lanes more popular, they are** safer** than streets without any bicycle provisions (3). And this is despite the fact that Montreal's bike lanes lack many of the measures now used to make them even safer: green markings through intersections, set back car parking and so on.

The petition writers are just bullshitting if they claim they know a bidirectional bike lane is more dangerous than what we have currently on Harbord. They don't have the evidence to make such a claim. Transport Canada references a Danish study but no link to the study. We don't know the context, when it is relevant, how to compare it to other dangers, or how various cities have made modifications to make them better.

Furthermore, their claim of "danger lanes" begs the question, if they're so dangerous why do numerous cities still have bidirectional bike lanes and continue to build them? Montreal, New York, Vancouver, Rotterdam, Amsterdam and other cities all have bidirectional with no evidence of cyclists dropping like flies so far as I tell.

Bidirectional versus unidirectional - either is fine so long as we get them

Funnily, the anti petition could perhaps hurt the anti cause. The petition says they are "in favour of keeping Harbord's current unidirectional bike lane setup".

The bidirectional bike lanes remove fewer parking spots than a unidirectional bike lane. That's one main reason why City staff are proposing bidirectional: to save some parking. If some people are against the bidirectional, perhaps we should all push for unidirectional. If it means taking out all the parking between Bathurst and Spadina so be it. Isn't that a small price to pay for increased safety?

I wonder what would happen to the unholy alliance in that case?

The world has moved on

Meanwhile, we could have had this already (photo by Paul Krueger):

While we're still fighting old fights in Toronto the world has moved on. In the last few years we've seen North American cities move far beyond painted bike lanes by installing separated bike lanes all over their downtowns. New York, Montreal, Vancouver, Ottawa, Chicago and other cities are all building separated bike lanes. City officials have official guides. Studies show that separation is both safer and more popular. Dutch and Danish cities have had them for decades.

It seems to me that by teaming up with anti-bike lane businesses the petition writers are playing a dangerous game (or should I say risky?) that is going to make it harder to build bike lanes of any kind anywhere in this city whether it stops the bidirectional lanes or not.

Footnotes:

1. The petition claims "According to research conducted by Transport Canada, experts conclude that bidirectional bike lanes are more dangerous than unidirectional bike lanes." I didn't receive any additional information, though I believe it's this link, which includes a reference to a Danish report that recommended unidirectional over bidirectional separated bike lanes saying bidirectional could create more conflicts at intersections. What the reference does not say is if the Danish compared bidirectional to painted or even no bike lanes at all.

2. Letters of support from: Cycle Toronto, the York Quay Neighbourhood Association, The U of T Graduate Student’s Union, University of Toronto Faculty Association, the Toronto Island Community Association, the St Lawrence Neighbourhood Association, the ABC (Yorkville) Residents Association, the Palmerston Residents Association, the Bay Cloverhill Residents Association, the Parkdale Resident Association, South Rosedale Residents Association, the Moore Park Residents Association, the Oak Street Housing Coop Inc., and Mountain Equipment Co-op.

*3. The study states: "our results suggest that two-way cycle tracks on one side of the road have either lower or similar injury rates compared with bicycling in the street without bicycle provisions. This lowered risk is also in spite of the less-than-ideal design of the Montreal cycle tracks, such as lacking parking setbacks at intersections, a recommended practice."